Today goes by many names. Veteran’s Day, Armistice Day, Remembrance Day, or here in France, simply “The 11th of November”. It was on this day in 1918 that that World War I ended. In France, even far from where the front lines used to be, the effects of the war are still very much present. In almost every village, no matter how small, one can find the monuments to the war dead. In Bussy-la-Pesle, which had only around 120 residents during WWI, the monument lists six names. It’s hard to comprehend the impact that so many deaths must have had on these villages.

* * *

This day also holds special significance for my family. While serving with Canada’s 25th Infantry Battalion, George Stuart Burchill – the brother of my father’s mother – died ninety-five years ago today from wounds received at the Second Battle of Passchendaele.

Aerial photos of Passchendaele before and after the battle.

In a war that is infamous for the inhuman conditions in the trenches, the situation around Passchendaele stood out as being particularly miserable. Aerial photos of the village taken before and after show that the village was completely obliterated by artillery fire. Combined with heavy rain, the artillery churned the ground into an almost impenetrable morass of mud and craters. In his superb book To End All Wars, Adam Hochschild provides a quote from a British officer that gives a glimpse of the difficulties of simply moving in such an environment:

Canadian machine-gunners in the front lines at Passchendaele, late October or early November 1917.

“A party of ‘A’ Company men passing up to the front line found … a man bogged to above the knees,” remembered Major C. A. Bill of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. “The united efforts of four of them, with rifles beneath his armpits, made not the slightest impression, and to dig, even if shovels had been available, would be impossible, for there was no foothold. Duty compelled them to move on up to the line, and when two days later they passed down that way the wretched fellow was still there; but only his head was now visible and he was raving mad.”

“The Mule Track” – Paul Nash

The phenomenal online collection at the Canadian Great War Project provides a detailed record of the actions of the 25th Battalion during the battle. Every official document that was preserved is there – orders, plans for the transportation of food and ammunition, arrangements for the synchronization of officers’ watches. The battalion’s war diary describes the weather, enemy activity, the way the mud softened the impact of artillery and gas, and, of course, the casualties. With the use of these documents, I’ve been able to piece together the last few days of my great-uncle’s life.

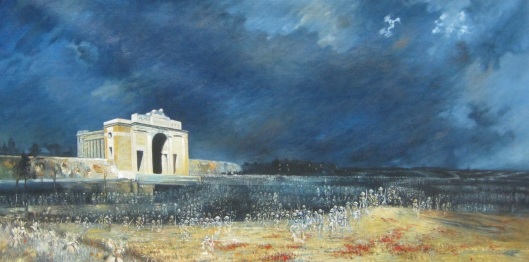

“The Ypres Salient At Night” by Paul Nash

On the night of November 7th, the 25th Battalion was ordered to move up to the front line trenches just east of the ruined village in order to relieve the soldiers stationed there. It was a distance of under 2 miles, and all of it through Canadian-controlled territory, but it took the 25th Battalion more than seven hours. Sometime during that journey, in a flare-lit landscape of shell-holes, shattered trees, and rubble, George Stuart Burchill became separated from his company.

He spent the night in an area that was being heavily shelled by German artillery, but when the morning brought enough light for him to see, he continued on to rejoin his company in the front lines. As he moved forward he was shot in the right arm and thigh. He was evacuated to a casualty clearing station behind the front lines, but that was not enough. Three days later, exactly a year before the war would end, my great-uncle died of his wounds. He was 19 years old.

The record of George Stuart Burchill’s death.

* * *

Ninety five years later, I’m standing in front of Bussy-la-Pesle’s memorial with a group of other villagers who have come for the Remembrance Day ceremony. Before the service begins I chat quietly with Quico, one of our neighbors. I tell him that I was impressed by the high turnout. Out of a population of around 70, roughly 35 people had come for the service. He nods, looks thoughtful, and then tells me, “Yes, but it doesn’t hurt that afterwards we’ll all go to the town hall for a drink.”

Two men step forward out of the crowd and go stand by the memorial. One of them, the mayor, clears his throat and tells us that it’s eleven o’clock, so we might as well get started. The other man places a pot of flowers in front of the memorial. The mayor presses a button on a remote control and music plays from a speaker in a nearby window. It’s a military march, the kind of thing you’d hear while watching old newsreel footage. The mayor reads the names on the monument while the other responds:

The monument for the citizens of Bussy-la-Pesle killed in WWI.

There’s a moment of silence, which to my mind is far better suited to the occasion than the military marches, then more music, similarly peppy. The mayor pulls out a piece of paper and reads something. We learn that this year France decided that Nov. 11th would be dedicated to those killed in all its wars, not just WWI. The mayor presses the button for the last time and The Marseillais plays.

The gathering after the memorial service.

And then, just as Quico promised, we all walk over to the town hall for kir (blackcurrant liqueur and white wine) and snacks. Even after two months in the village, this is the first time I’ve seen some of these people. But even to an outsider, the warmth of a tight community comes through clearly. We talk, me with my broken French, and they with their patient curiosity. Yes, it is a charming village. Did you know that there are seven artists who live here? You come from Vermont? That’s near Quebec, isn’t it? How long are you here? Oh no – you leave so soon!

It’s a good thing, this gathering.

* * *

“We Are Making A New World” – Paul Nash

Paul Nash, a British painter who served in the First World War and was commissioned as a war artist, produced some of the most striking imagery to come out of that war. One painting in particular resonates with me. Titled “We Are Making A New World”, it depicts the sun rising over a war-torn landscape of shattered trees and shell holes. The title by itself suggests optimism, but paired with the image, the result is bitter irony.

This century is still in its infancy, and who can say what new world the coming years will bring? There are certainly reasons for hope. But a hundred years ago, few could imagine that they would soon be engulfed in a conflict that would dwarf all earlier wars. And in 1919, when we spoke of “The War to End All Wars”, few guessed that twenty years later would come another, larger still. We’ll face our share of challenges in the coming years, and I hope that we find a better way to address them than did our predecessors.

For me, that is what today is for. To remember the awful cost of war, and to commit ourselves to finding better chisels for carving out peaceful tomorrows. And if it means that we get a bit of kir while we’re at it, well, I can live with that.