My family visited our friends friends Antoine and Cecile in Cassel, a walled town that rises almost six hundred feet above the flat land all around. A landmark like that is inevitably steeped in history. Recognizing its geographical importance, the Romans built a system of roads that converge on the town. Throughout the middle ages Cassel was fought over again and again, by dukes and counts and kings of France and Flanders and Spain, the Netherlands… The German advance in World War I ground to a halt just shy of Cassel, and allied commanders used the town as their headquarters. In May of 1940, British forces took a stand at Cassel to delay the German advance, thereby buying time for their comrades to be evacuated from Dunkerque, just a few miles to the north. From the hill on which Cassel is built I looked out over the fields of Flanders. From 1914 through 1918 I would have been able to see the front lines to the west, a shell-torn scar across the land. The rumble of artillery would have been constant, and at night the horizon would have been lit by flares and explosions.

Today marks a century since Germany and France declared war on each other and opened the Western Front of World War I. I’ve already written about France’s memory of the war and my family’s connection. My great uncle died in November of 1917 after being wounded at what was left of the small village of Passchendaele during the Third Battle of Ypres – just a few miles from Cassel. Antoine took Julian and me to visit his grave, located in one of the many cemeteries that are scattered throughout the countryside, each one corresponding to a casualty clearing station or field hospital.

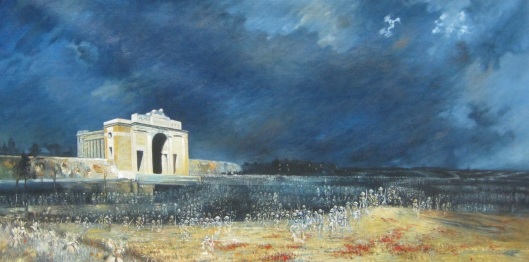

One night we walked through the old city of Ypres, which had been the focal point of fighting throughout the war. Commonwealth soldiers headed to the front passed through the city and marched east. That road is now marked by the Menin Gate, a memorial dedicated to the Commonwealth dead “to whom the fortune of war denied the known and honoured burial given to their comrades in death.” The bodies of 90,000 soldiers from Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India, and other British colonies simply disappeared into the mud of the Ypres Salient. The names of 55,000 of those soldiers were carved into the walls of the Menin Gate before the builders ran out of room.

The heart of Ypres had been the Cloth Hall, a magnificent gothic market hall built during the 13th century. By the end of WWI, four years of constant shelling had reduced the building to an unrecognizable ruin. But along with the rest of the city, it was carefully rebuilt, and the city center thrives once more. As we walked past the rebuilt Cloth Hall and through the Menin Gate we heard a low rumble in the distance, but it was only thunder.

For those who are interested in learning more about the First World War, I strongly recommend The Atlantic‘s superb photo series.